One thing that people often don’t understand about mineral ownership is how the oil and gas company can sign a lease with one family member and not have to sign a lease with another. Isn’t the oil and gas owned by both/all of you? When my siblings sign, does that mean the oil and gas company doesn’t have to sign with me? Can I still negotiate with the company if my siblings have signed?

One thing that people often don’t understand about mineral ownership is how the oil and gas company can sign a lease with one family member and not have to sign a lease with another. Isn’t the oil and gas owned by both/all of you? When my siblings sign, does that mean the oil and gas company doesn’t have to sign with me? Can I still negotiate with the company if my siblings have signed?

It’s confusing to a lot of people. It took me a while to wrap my head around it, too. But I understand it now, and so can you. Here’s how it works.

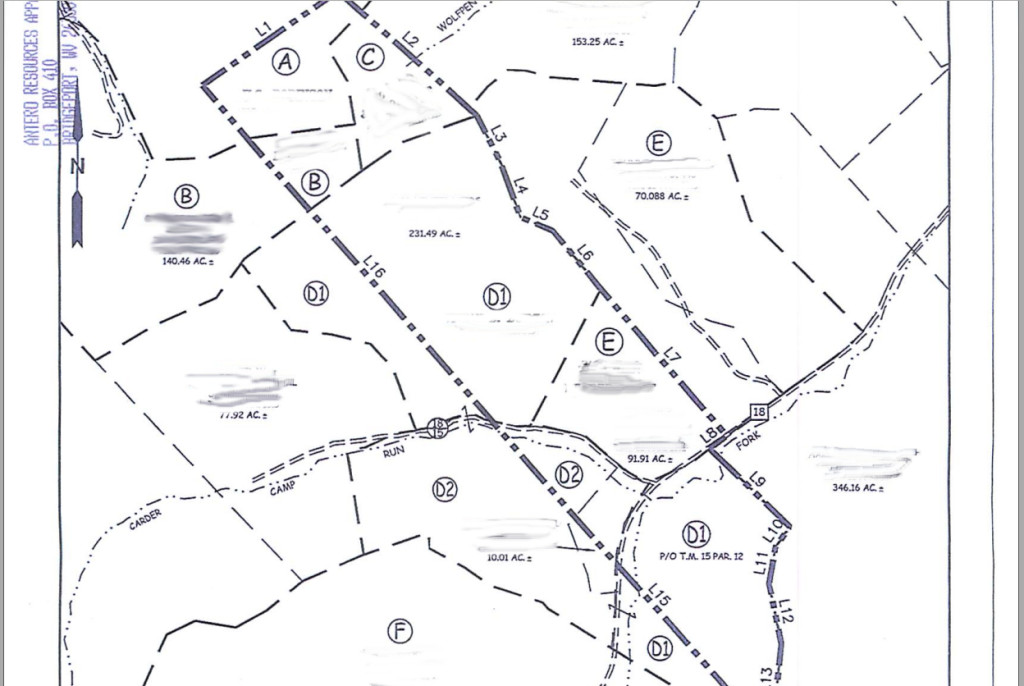

Usually you will inherit the oil and gas underneath one tract of land here in the great state of West Virginia. (Sometimes there are more, but let’s keep it simple for now.)

Let’s set up a simple scenario to work with. Mom owned a 30 acre tract of oil and gas rights. She had three children. When she passed away the 30 acre tract passed down to the children.

Most people think that since there are three children who own an interest in the tract, then you can divide the tract into three equal parts of 10 acres each and give one part to each child. The 10 acres that are at the top of the hill go to the first child, the 10 acres that are in the “holler” (this is West Virginia after all, the valley is a holler) go to the second child, and the 10 acres that are in between go to the third child.

That’s not how it works, though.

The children own the oil and gas that’s below the 30 acre tract together. Each child has an interest in each molecule of gas. Each molecule of gas has three owners.

So you can’t draw lines on the map to make 10 acre tracts and give each child one. (There is a way of doing this, called a partition suit, but it’s not necessary to get into right now.)

Since each molecule of gas has three owners, no molecule of gas can be removed from the property or sold without the permission of every person that has some ownership of that molecule of gas.

Since there are three separate owners, the oil and gas company has to deal with each owner. The company has to get a separate contract with each owner.

The example that seems to help most people understand all of this the best is that of an old-fashioned encyclopedia. You can buy and sell the books separately. You can pay different prices for each book. You can buy one this month, another next month, and a third the month after that.

But you don’t have the entire encyclopedia until you’ve bought them all. This is important in West Virginia, because under West Virginia law the oil and gas company can’t do anything with the oil and gas until it owns all the “books”. The company can’t drill, produce, and sell the oil and gas until all the owners have agreed to do so.

Knowing that, here are the answers to the questions above.

Yes, the oil and gas is owned by all of you. However, none of you own or control in any way your siblings’ interests.

Yes, the oil and gas company has to sign a lease with you even when your siblings have already signed agreements. West Virginia law requires this.

Yes, you can still negotiate with the oil and gas company even though all your siblings have agreed to something different. We regularly get more money and better royalties for the siblings who decide to negotiate with the oil and gas company.

If you own oil and gas in West Virginia and need help understanding things, give the office a call at 304-473-1403.