Bloomberg has an interesting article about old wells in Pennsylvania and how they can affect or be affected by a horizontally fracked well.

West Virginia has the same problem.

The first thing to know about old wells in West Virginia is that we don’t know where they all are. West Virginia didn’t start assigning API numbers to wells until 1929, at least forty years after oil and gas development really boomed in West Virginia, and at least seventy years after the first oil wells were drilled. That means there are a lot of well locations out there that are unknown. How many?

A quick Google search turned up some great photos that can help us get an idea. The following were taken from a web site about the Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad. There are many more on other sites.

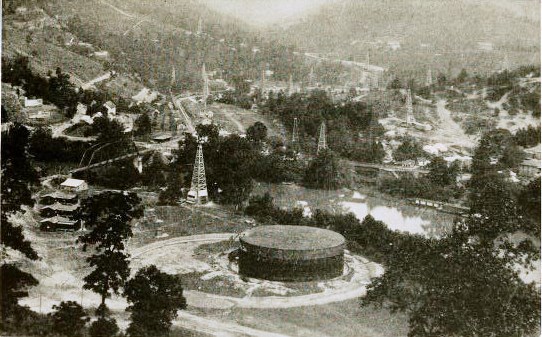

The photo below was taken in 1913 on Blue Creek in West Virginia. You can plainly see at least six wells, and possibly another six or seven. When you look at the larger photo it’s possible that some of what looks like oil derricks are actually just ageing or smudges on the photo.

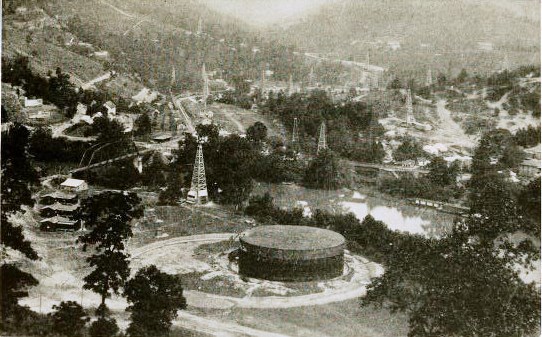

This photo of oil wells in West Virginia was taken at another location on Blue Creek, possibly about the same time as the one above. There are clearly ten oil wells.

None of those wells would have had API numbers, and their locations were never recorded by anybody. Nobody thought they would be important. They are the kinds of wells that we are concerned with, and they exist all over West Virginia.

Many of these old wells were not properly plugged when they were abandoned. Someone might have thrown old lumber or trees down the hole, filled it with dirt, and called it a day. Others might have gotten a little better treatment with some cannon balls or scrap metal thrown in for good measure. Very few were plugged with cement, and many were just left open.

This can be a real problem when a horizontal well is drilled nearby. Some of the old wells were drilled down thousands of feet, a few even into the formations that we are fracking today. When we frack, the pressure can push fluids into the old wells, either directly by way of the induced fractures or through existing faults in the rock. It’s called well communication in the industry.

It could lead to contamination of a water well, or fracking fluids on the surface, or natural gas spewing into the air. Nobody wants that. Even the companies doing the fracking don’t want that as it lowers the amount of pressure in their well, leading to fewer, shorter, and smaller fractures and lower production.

So what can be done about it? It’s hard to do much about it. Many of these old wells don’t show above the surface, so getting eyes in the field isn’t going to help. A metal detector will find a lot of them, but some of these old wells were lined with wood. Even the wells the were lined with metal often had the casing pulled out for use on another well. It’s a real problem, and there isn’t an obvious and good solution.

The reason we’re writing about it is to point out to people one way that their water wells can be contaminated with fracking fluid. If you think you have a water well that’s been ruined by fracking you can get help. It’s going to be an uphill battle proving that fracking did it, but it can be done.

Call the office at 304-473-1403 and find out what you can do.

We’re in favor of developing oil and gas resources. However, not everyone is. If you don’t ever want your oil and gas developed, then

We’re in favor of developing oil and gas resources. However, not everyone is. If you don’t ever want your oil and gas developed, then