For most of my clients, getting a Pugh (pronounced “pew”) clause in their lease is going to be tough, but worth it. It’s tough because oil and gas companies don’t like to give Pugh clauses to people who have a tiny net mineral interest in a large tract. It’s worth it because a Pugh clause makes it so you can regain control of your mineral rights.

For most of my clients, getting a Pugh (pronounced “pew”) clause in their lease is going to be tough, but worth it. It’s tough because oil and gas companies don’t like to give Pugh clauses to people who have a tiny net mineral interest in a large tract. It’s worth it because a Pugh clause makes it so you can regain control of your mineral rights.

A Pugh clause comes into effect at the end of the primary term of the lease. On that date, any portion of the property that is not actually producing oil or gas will drop out of the lease. Here is why that’s important.

Every oil and gas lease has a primary term. Most leases taken in West Virginia of late have had five year primary terms. The primary term is the period of time during which the oil and gas company can explore, drill, and perform work to achieve production of the oil and gas. At the end of the primary term, if there’s no production, there’s no lease. If there is production, the lease continues.

Every oil and gas lease also has language in it that says if part of the leased property is producing oil or gas, then all of the leased property will stay leased. In the industry, we say that it’s “held by production” or HBP for short.

Every modern oil and gas lease gives the company the right to combine the leased tract with other leased tracts to form a drilling unit or a pool. (While there’s a difference between units and pools, it’s not necessary for understanding a Pugh clause.) That unit or pool can include all or just a part of the leased tract. Only the part of the leased tract that is in the unit or pool is going to have royalties paid on it, as only that part of the leased tract is considered to be producing gas. Any little part of the tract could be included, down to one square inch, and it would still keep the lease alive on the entire tract.

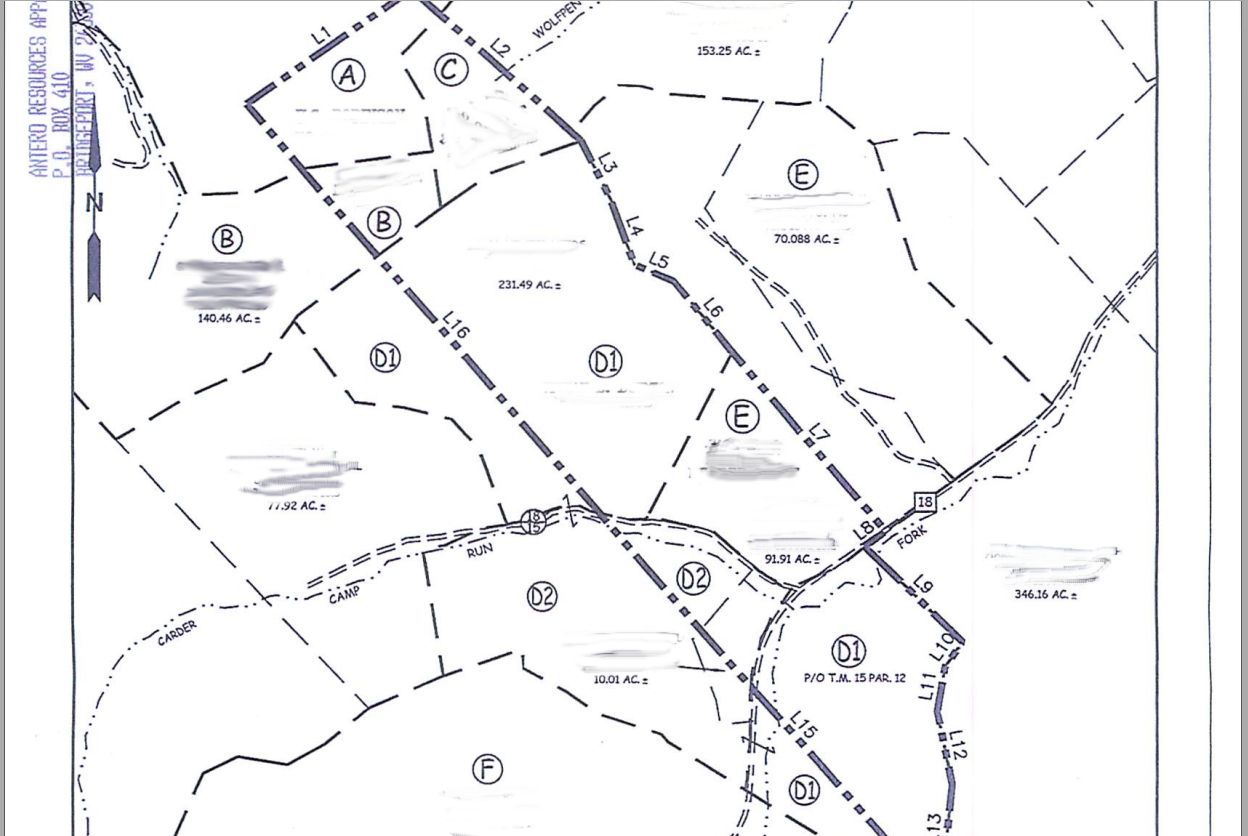

I’ve posted a picture of a real drilling unit above, one that’s been filed at the Doddridge County courthouse and is actually producing gas today. I’ve redacted any identifying information, except for Antero Resources, since they want people to get in touch with them. Notice Tract B in the upper left hand corner. Only a portion of that tract is included in the drilling unit. Only that portion of the tract is going to have royalties paid from the drilling unit. The rest of Tract B will be held by production for as long at the unit is producing oil or gas.

In real life Antero is going to be putting the rest of Tract B into another unit that is right next to this one. However, if things don’t go according to Antero’s plan, it’s quite possible that the rest of Tract B could have a lease on it for decades without producing gas, and consequently, not producing royalties or any payments of any sort. That’s neither fair nor right.

That’s where a Pugh clause comes into play. A typical Pugh clause will say that any acreage that’s not producing at the end of the primary term will drop out of the lease. When the primary term is up, the mineral owner will get the right to lease the property again, hopefully with a better bonus and a better royalty amount. The mineral owner won’t have to sit around wondering whether the company is going to develop the minerals or not.

There’s one more point that needs to be made. A Pugh clause can also state that any formations which are not producing will drop out of the lease. This is extremely important in West Virginia as there are multiple shale formations with the potential to produce oil or gas under most of the acreage that is being leased today. Most people know about the Marcellus Shale and the Utica Shale. There is also the Barnett Shale, which is a little shallower than the Marcellus Shale. There are other Upper Devonian formations (the Marcellus and the Barnett are both Upper Devonian formations) which could potentially produce gas or oil. There is also the Point Pleasant formation, which is directly below the Utica Shale. In the western part of the state there is the Rodgersville Shale, the Berea sandstone, and the Trenton-Black River which are currently being explored. There is also some work being done to explore traditional shallow oil formations for possible oil production using new techniques. At this point, we simply can’t say how many formations are down there that could produce oil or gas. So it’s important to get a Pugh clause that says formations drop out, too.

For the large majority of my clients, it’s going to be difficult to get a Pugh clause because they own such a small portion of the minerals. Most oil and gas companies are not going to give up the rights to a small portion of the tract at the end of the primary term for one person when everyone else has agreed to a lease without a Pugh clause in it. The companies will give a Pugh clause if they get desperate, though. Sometimes it’s worth it to push the issue. Of course, you have to balance the importance of a Pugh clause with other considerations as well.

In short, get a Pugh clause if you can, and make sure that it affects both acreage and formations.

If you find yourself in negotiations and think or feel that you need help, give my office a call. It’s what we do.